That is speculative, exploratory espresso science. Please don’t take it as gospel and even really useful. Disagreement is sweet and debate pushes us additional to the boundaries of espresso.

First crack holds almost a mythical status for coffee roasters: it’s the moment the flavour and structure of the coffee beans really begins to develop, and heralds the part of the roast when the roaster has to pay the closest attention to the roast curve, making minute adjustments with split-second timing to ensure the coffee follows its profile exactly.

And yet — is it possible that neither first crack, nor the precise adjustments to the gas settings that roasters make afterwards, are actually very important in coffee roasting?

In a brand-new White Paper for Barista Hustle, published yesterday, multidisciplinary scientist and occasional coffee provocateur Professor Steven Abbott introduces a new feature for his coffee roasting simulator that is sure to be controversial in some circles: the two-step model, designed to help roasters eliminate the need for micromanagement at the end of a roast. Perhaps even more controversially, he casts doubt on the importance of first crack in coffee roasting — calling it ‘The Last Gasp’.

The Two Steps

Put simply, the idea behind the two-step feature is, no matter how complex a roast profile you design for a drum roaster, you could achieve more or less the same effect with just one single gas change. The idea is that once you’ve designed the perfect roast profile for your coffee, you can use the app to work backwards and find a much simpler way to achieve the same results — assuming that you know enough about your roaster and your beans.

That last part, of course, is a huge, unsolved problem. Part of the reason that specialty roasters need to babysit coffees through a roast, instead of just using a fixed profile, is that beans can behave unpredictably. Each coffee will respond differently to the same roast profile, and even different batches of the same coffee will throw you a curveball from time to time.

For this reason, we need signals that can tell us how fast a roast is progressing in real time. In traditional roasting, the key signals are sight, smell — both rather subjective — and of course the two major milestones of first and second crack.

First crack plays a pivotal role in many roasters’ philosophies. Whether you’re talking about development time or time-to-first-crack, deciding when to apply a ‘gas dip’ or avoiding the ‘crash’ and ‘flick’, the timing of first crack has a big effect on how a roast profile is designed.

And yet in industrial practice, first crack doesn’t seem to be that important. In large air roasters it’s common practice to use a flat temperature for most or all of the roast, and simply drop the batch at a specified end temperature. This approach might not be optimal — after all, some research shows that the whole roast profile matters, not just the time and temperature (Gloess et al 2014) — but it sure is simpler.

Perhaps specialty roasting could also be made much simpler, using approaches like Professor Abbott’s two-step simulation, if we knew more about what happens around first crack?

Counting the Cracks

At some point during your barista career, you’ve probably heard the pop of first crack being described as similar to popcorn. It’s actually very different to this, in two crucial ways.

Firstly, the beans don’t suddenly explode in size at first crack the way popcorn does. Coffee beans expand gradually during roasting. At a certain temperature the bean structure gets soft enough, and the gas pressure inside the bean gets high enough, that they start to inflate like little balloons. This goes on all the way until first crack — at which point you might see one or two just change shape, or even deflate slightly, as they pop.

You can see this happening in this great video by Thompson Owen from Sweet Maria’s. Start the video at around 5’44”, and you can watch beans going through the whole roasting process from green through to second crack.

As you will notice, the beans increase effectively earlier than first crack, and at first crack itself they just pop open, rather than puffing up further. So whatever is happening, it’s not the same thing that happens in a popcorn popper. For more details about what the causes of first crack might be, you can check out the chapter on first and second crack in our Roasting Science course.

The other big difference to popcorn — and perhaps the biggest surprise for many roasters — is that only a small fraction of beans even seem to go through first crack at all. You might notice this in Thompson Owen’s video above; not all of the beans show any sign of cracking. There are somewhere between five and ten thousand beans in a kilogram of coffee — but how many pops do you hear during roasting?

Some scientists have investigated this, using microphones to record the sound of first crack and using a computer algorithm to count the number of pops. One researcher roasted 230 grams of coffee and recorded just 62 audible ‘pops’ (less than 5% of the beans) during first crack and 241 pops (less than 20%) during second crack (Wilson 2014). Another estimated that 7% of beans pop audibly in first crack and 13% during second crack, but pointed out that you get more pops if you roast at higher temperatures (Yergenson 2019).

The number of pops also depends on the beans you are roasting: As Professor Abbott observes, ‘some beans roast perfectly well with no audible crack’. On the other hand, some beans crack more violently than usual: this short clip from coffee roaster and scientist Mark Al-Shemmeri shows one particularly boisterous Mexican bean jumping in the trier.

Watch the bean in the lower-right hand corner jump as it enters first crack. Video courtesy of Mark Al-Shemmeri.

A More Meaningful Milestone

First crack is the most important reference point in how a roast is progressing simply because it is audible — so there’s very little argument about when it takes place. Other common measures of bean development, such as weight loss, are virtually impossible to measure in real time in a roaster. But new technologies offer more flexible methods to measure how beans respond to roasting, which could give us new, more useful markers to refer to in a roast curve.

The most obvious method for monitoring a roast in real time is to measure the colour of the beans during roasting, using a sensor to give an objective reading of the beans’ surface colour. The technology for this already exists in coffee — many prominent roasteries use ColorTrack devices, for example, to help them monitor a roast and decide when to end a roast.

Colour has some major limitations as a roast marker, however. The colour of the coffee depends not just on the roast, but also on the type of coffee — for example, decaffeinated coffees are darker than their regular counterparts at the same roast level (Al-Shemmeri 2023). The link between colour and degree of roasting (as measured by the weight loss of the coffee) depends on the temperature profile of the roast, so it’s not an absolute measure of the degree of roasting (Yergenson 2019). Furthermore, colour meters can be affected by ambient temperature, or might give different readings as the coffee degasses over time.

Another method is to use near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) — a technique that is similar in some ways to using a colour meter, but based on infrared radiation instead of visible light. Yergenson (2019) found that by measuring two specific wavelengths of IR, it’s possible to predict the degree of roasting across different coffees and roast styles, and thus predict the onset of first crack in a coffee before it takes place. Such techniques may even help predict and control the amount of acidity in a coffee independently of the degree of roast — in other words, to allow you to moderate the acidity of a light roast, or heighten the acidity of a dark roast, by manipulating the profile.

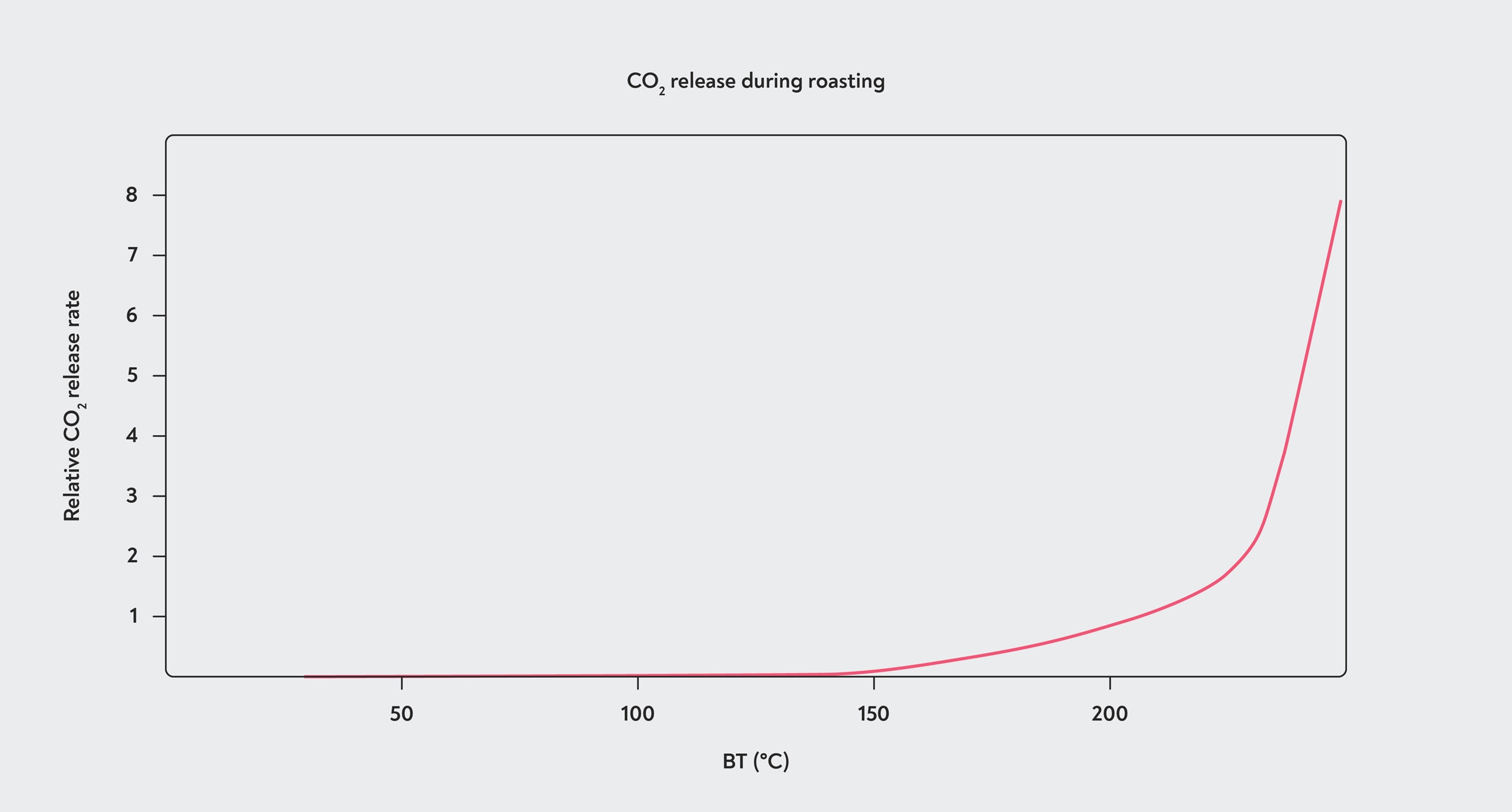

A third option, suggested by Professor Abbott in the White Paper published today, could be to measure the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) and/or carbon monoxide (CO) released during roasting. There’s hardly any research linking the amount of CO2 and CO released to the roast progression in real time, but the data that is out there suggests that the rate of release increases over time, depending on when the different chemical reactions in roasting kick in, so the amount of CO2 and CO in the exhaust could give some indication of what reactions are taking place at that time.

Professor Abbot’s estimate of the relative rate of CO2 release during roasting, based on published data from various sources (but not direct measurements). As the bean temperature rises, the rate of CO2 release increases.

Professor Abbot’s estimate of the relative rate of CO2 release during roasting, based on published data from various sources (but not direct measurements). As the bean temperature rises, the rate of CO2 release increases.

All of these methods will take a lot more research and development before they could become as important to a roaster as listening out for first crack is. There may come a time, however, when we can use chemical changes in the beans — rather than the much more variable signal of a few quiet pops — to know where we are in a roast. Being able to predict ahead of time exactly when first crack will happen will surely give roasters much better control over their roast profiles, even if first crack itself turns out to be less important than we thought.